Clay Kohut’s pitch for his new app, Ameego, is so absurd that it’s best to let him deliver it.

“With Uber, you rent a stranger’s car,” he begins.

“With Airbnb, you rent a stranger’s home.” Mhmm.

“With Ameego … you rent a stranger!” What?

“It’s a logical progression,” he reassures.

The Texas-born developer and entrepreneur is, as you may have suspected, a full-on millennial, just shy of 26 years old. He’s a member of a generation in which “progress” follows slightly different rules. Upon sensing a problem – such as, say, the glut of young people who find themselves in new cities, without their old friends – Kohut and his cohort hesitate but a moment before deploying apps to solve it.

In the past month, this class of fresh-faced entrepreneurs has launched the buzzy Hey! Vina, an app that “helps women find new friends,” Bro, an ambiguous social-network-slash-dating-app for “men interested in meeting other men,” and Rendezwho, which connects distant people through a series of “Buzzfeed-style questions.” They’ve pitched start-ups with self-explanatory and slightly pathetic names, like “LykeMe” and “Woez” and “Go Find Friends.” They’ve attempted a “Tinder for meeting people” and a “Meetup for spontaneous get-togethers.”

Those last two failed. Ameego won’t, Kohut insists.

“We’re the first ones to commodify friendship,” he says.

Kohut will admit, if reluctantly, that not all things should be commodified. (In fact, his hope for Ameego is that, after a few hours of paid companionship, the professional friend and his client will become pals in real life.) But he also realizes, like any savvy entrepreneur, that he’s offering a service valuable enough that some people will pay for it. After all, what millennial hasn’t found herself friendless or flaked-on at some point, thumbing desperate texts to a BFF who’s still in Pittsburgh or Des Moines?

“I don’t think it’s at all clear that our social networks are larger or smaller than they have been in the past,” said Keith Hampton, the co-chair of the Social Media & Society program at Rutgers University. “But in general, people do report having fewer closer friends and confidants than they may have had previously.”

Hampton’s research focuses on the way that technology impacts our social relationships – or, in many cases, how it appears to but doesn’t. The recent spate of friend-making apps is a prime example of the latter. While these app’s creators frequently believe they’re fighting tech-induced isolation (“no one leaves their computer long enough to meet people,” Kohut explained to me) the case of the declining friend count is actually far more complicated than that.

For one thing, Hampton has found, people in affluent societies with strong safety nets tend to have fewer closer friends — which suggests that, as the US has industrialized and developed, successive generations have friended fewer people, probably without realizing it.

On top of that, our social networks have become less centralized, a change dating back to the aftermath of World War II. Where close ties were once based on strict geographic locations – a neighbordhood, an office, a church – people have become more mobile, and their networks both more individualized and more ambiguous.

Add to that the peculiar wrinkles of growing up in the aughts – an economy that’s kept many living with parents or, alternately, moving far from the people they know; a collapse of institutional power that’s left many without a local social hub – and it’s little surprise that 11 percent of adults aged 18 to 37 claim their relationships with friends don’t bring them happiness. Many belong to vast social networks, with ties that span multiple countries and life stages; but they don’t, on any given day, have anybody to hang out with.

It’s a paradox that the fast-talking, amiable Kohut has experienced himself.

“I was 19 when I dropped out, left my small town in Texas, and moved to New York,” he said. “If someone told me they could give me the ability to instantly make new friends, I certainly would have paid for that.”

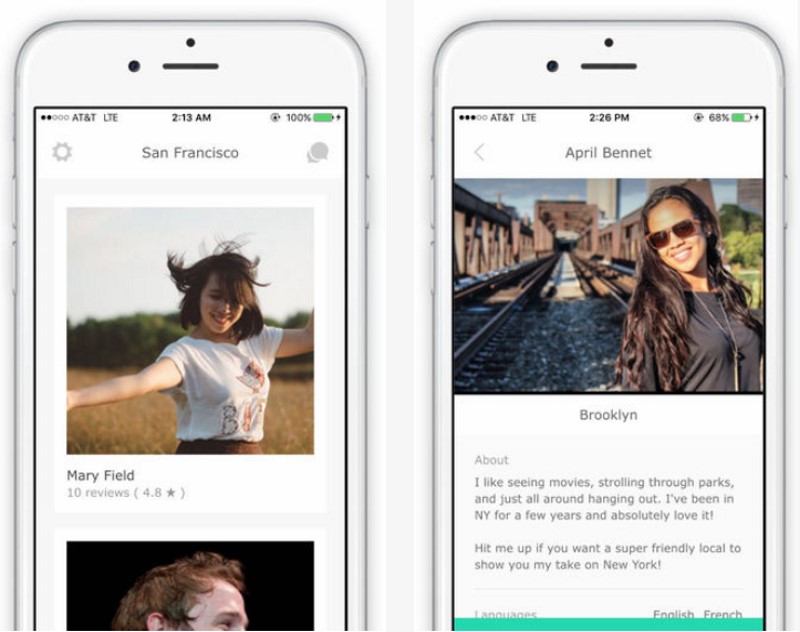

Will anyone else? That remains to be seen; Ameego is currently available in New York and San Francisco, with prospective plans to launch more widely in the future. When it does, it will find itself up against not only other dedicated friend-making apps, but a whole range of millennial-marketed technologies that attempt to connect local strangers: MeetUp, Nextdoor, Mico, Skout, Yik Yak, Tagged, Tinder. In 2015, 57 percent of teenagers had met a friend online, according to the Pew Research Center.

Some of the Olds in the audience may tut at this: Can’t these kids make friends without their phones? But it’s not that social skills have declined or anything like that. It’s that digital natives are reconstructing online the meeting spots and adjacencies they don’t have in the real world. Already, some research suggests that people who use social media have more friends, and see them more frequently, than people who don’t. And Hampton, for one, thinks that further online connections between nearby strangers would benefit their communities and neighborhoods.

“When you build up local social ties, that has implications for collective action, community solidarity – even emergency situations,” Hampton said. “Whether those relationships begin online or off, it starts to solve some of the problems related to the loss of close social connections.”

© 2016 The Washington Post

Download the Gadgets 360 app for Android and iOS to stay up to date with the latest tech news, product reviews, and exclusive deals on the popular mobiles.