The world’s leading management conference—the Global Peter Drucker Forum—met last week in the Imperial Palace in Vienna Austria for its eleventh annual get-together. As in previous years, discussions at the Forum confirmed that a large-scale movement to transform management is under way. The management practices of the most successful companies today are very different from those of the 20th Century, even though overall innovation performance across the economy is still poor.

“What is changing,” said Julian Birkinshaw, Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at the London Business School, “is the practice of management… We are seeing a lot of experiments with new ways of working. It’s not only the Ali Babas, the Amazons and the Googles, but also a lot of traditional companies who are experimenting. It’s not just a story of digital innovation. It’s a story of new business imperatives, causing companies to do different things.” Among the firms he cited were Haier, Tencent and Pixar.

The Case Of Haier

Zhang Ruimin, CEO and Chairman of the Board of Directors, Haier Group, which is now the world’s largest appliance business, having bought out GE’s “white goods” business, has said that “the biggest risk facing organizations is to focus on their product, meaning if they were not focusing on iteration, if they were not thinking about a broader ecosystem of customer experience, they were going to be left behind.” He said that “ecosystems” here meant “multi-company systems that bring together partners, animated by a belief that collaboration is needed for innovation and business.”

At the conference, Zhang Ruimin declared that unless our firms transform into ecosystems, they won’t survive. Haier wants to transform from being the world’s largest appliance manufacturer of “white goods” to being an ecosystem. Haier has been progressing towards that goal for over a decade. In the future, single stand-alone products are no longer valuable. What’s more valuable is a user-case scenario, where all of the appliances are connected with each other. What users want is the best user experience, which requires the connection of many different products. It’s a shift from mass production to mass customization.

Haier is building “an Internet of food” which connects appliances which can talk to food producers and recipe providers, so that customers are not just using the appliances but also have the best food experiences. It’s no longer just about a product but a user-case scenario.

Haier is also building “an Internet of clothing” so that you no longer just have a washing machine but also access to detergent and clothing manufacturers and chips which give users information about how to take care of their clothes. Haier is creating international standards for the “Internet of clothing” that enables firms like P&G to participate and benefit, even though they are also Haier’s competitors.

Haier is also working towards “the smart home” where customers are no longer selecting single products, but an entire set of solutions. The purchase is not just a few hundred dollars but instead, some sixty thousand U.S. dollars—something that could not be achieved by just a single product.

Moreover, the products all have sensors so that Haier can interact with the users and can iterate and continue to improve the experiences, so turning customers into lifelong users. In the product model of the firm, the relationship with the customer was transactional and was complete once the sale was made. In the new model, the completion of the sale is the beginning of the relationship. The sale is not a zero-sum game, in which the firm tries to win. In the ecosystem model, the goal is to provide value for all the participants.

In its organization model, Haier aligns its employees with the needs of the users, while also aligning the value the employees create for the customers with the gains to be shared with those employees. Haier has eliminated some 12,000 middle managers and created thousands of micro-enterprises, each of which has 8 members and is able to talk directly with the users. Zhang Ruimin agreed with Peter Drucker that in the 21st Century, “everyone will become their own CEO.”

The Case Of Tencent

In a session chaired by management writer and editor Julia Kirby, Arthur Yeung, Senior Advisor at Tencent Holdings, said that his company is a social network company with more than 1.5 billion active users and more than 700 million users with its social platform. The interaction takes place through games, video and music, The firm also provides services to firms with Cloud and social advertisement.

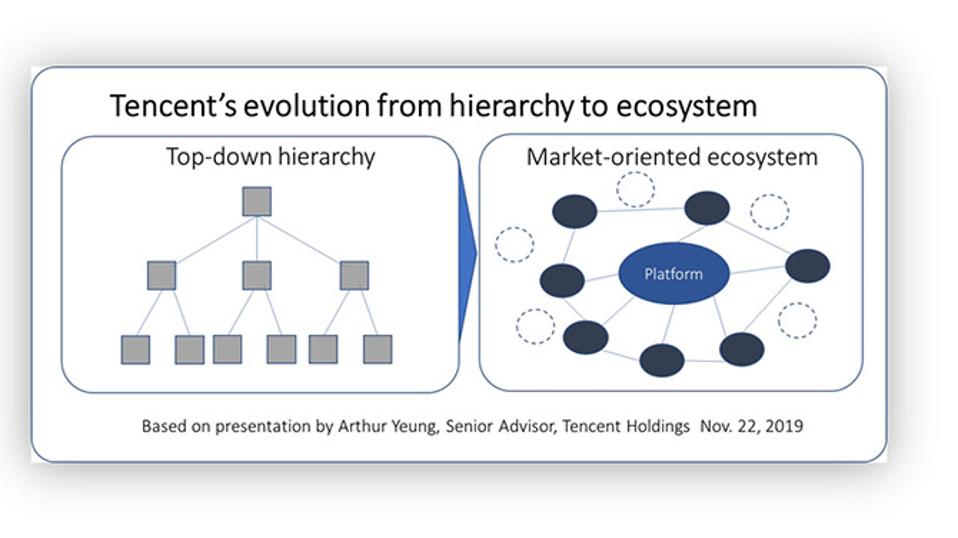

Tencent’s journey from hierarchy to ecosystem

STEPHEN DENNING

As Tencent’s business grew in size, Tencent struggled to maintain agility, innovation, and the customer obsession necessary for the firm to survive and thrive in an increasingly competitive and fast-changing environment. Because its games were successful, the studios were getting bigger and bigger, with a lot of layers, which slowed down decision making, due to multiple approvals. Cross unit collaboration was also difficult. Competition increased as new players had access to an abundant supply of capital and access to markets. Attracting top talent became a problem too. Even existing talent was leaving Tencent to launch startups. That was the situation 5-6 years ago.

So Tencent used “ecosystem logic” to redesign the organization. The large studios were broken into small autonomous studios. They were fully empowered so that they became agile, with a lot of bottom up initiative, rather than waiting for a lot of approvals.

The Case Of Google

Vint Cerf, VP and chief Internet evangelist at Google, said that the most important things about ecosystems were their stability, their inter-operability, and their ability to adapt to and accept change. Think about Lego and all the new parts that come along: even though they are specialized and different they all fit together. So Google is very concerned with making sure that ecosystem works well.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – MAY 13: Vint Cerf speaks on stage at The 23rd Annual Webby Awards on May 13, … [+]

GETTY IMAGES FOR WEBBY AWARDS

Before the Internet, there were a bunch of networks that didn’t work together. Then the Internet came along and connected them together so that everybody could take advantage of that. This is now happening in the Cloud space too. It is now possible to use Kubernetes or “containers” that enable you to write software that runs in multiple Clouds, and allowing different Clouds to interact with each other. So there is a path that allows collaboration and cooperation even while we are competing with each other. That helps everybody. Now you don’t feel trapped in some particular piece of an ecosystem. Cerf sees an opportunity to avoid the extremes of monopolization or fragmentation.

The Case Of Pixar

Ed Catmull, co-founder of Pixar Animation Studios, is a retired American computer scientist and former president of Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios. Catmull contributed to many important advances in 3D computer graphics.

BEIJING, CHINA – JANUARY 20: President of Pixar Edwin Catmull speaks at Geek Park Innovation … [+]

VISUAL CHINA GROUP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Catmull defines “creativity” broadly as solving problems. This is largely a group effort. People are the base of each company. Our job is to bring out the best in all of those people. There are a lot of things that have to be figured out. One of those things is removing power from the room. Those who are trying to solve the problems are in a very vulnerable state, because the problems are unsolved when they start. There is a need to ensure that the least powerful person in the room feels safe to talk. This is also a message to the powerful people who are expected to talk.

A second challenge concerns how to get full engagement. People follow the unspoken cues of the organization, following what the management does, not necessarily what the management says. Often the management doesn’t recognize the importance of what it doesn’t see. The problems remain unspoken. Managers underestimate the importance of what they can’t see and over-value the importance of the values they can clearly see. Pixar has been working on these ideas for many years and is still searching for they don’t know. By opening up to what they can’t see, people become more creative.

The Dismal Overall Performance In Innovation

Yet beyond these bright spots, the overall organizational performance in terms of innovation is poor. The session chaired by Curt Carlson, former CEO of SRI International, on “Cultivating Entrepreneurial Hotbeds,” looked more broadly at the overall scene and shed light on this darker side of change. Carlson noted Peter Drucker’s most famous dictum, “There is only one valid purpose of a corporation: to create a customer.” The two primary functions of a company are innovation and marketing: everything else is cost. Innovation is the primary path to growth, prosperity, meaningful jobs, and resources for social responsibility and defense.

We hear more, said Carlson, about the successes in innovation than about the failures. The U.S. has 1,300 incubators and most of them lose money. Almost all tech transfer programs in America lose money. National lab work produces little of value. Most venture capitalists lose money: 5% of venture capitalists generate 95% of the gains. Even within companies, less than 30% of the innovations being worked on have any value. There is therefore a need to profoundly improve innovation performance.

As to what could be done to create an innovation ecosystem, Carlson’s panel pointed to advances in AI and 5G, which will make the world more open and transparent to increase collaboration. He also pointed to the case of Singapore. This tiny country, starting from a low base, with no geographical space and no natural resources, now has average per capita income on a parity basis higher than the U.S.

In the session, Tony Tan Keng Yam, former President Singapore, explained how Singapore had to rely on human effort and ingenuity to build its economy. He noted three key elements in building an entrepreneurial society. First was the role of the government as the enabler. Second was the role of the private sector as a partner. Third was the role of society in inspiring its youth. Of note, Singapore is now promoting experiential project-based learning, a major change, to better prepare graduates for our world.

‘The Power Of Ecosystems’

The Forum’s theme was “The Power of Ecosystems.” Are ecosystems the answer? It was disconcerting to have the editor-in-chief of Harvard Business Review, Adi Ignatius, kick off the opening session with a reminder that “ecosystem” had been identified almost a decade ago by The Muse as the world’s most annoying buzzword, a term that “the whole office would be better off without.” It could be a useful way to describe something with a lot of interconnected, moving parts. “But most of the time, ‘industry,’ ‘network,’ or simply ‘system’ works just as well.”

In the course of the conference, speakers explored the many forms of ecosystems, both personal and institutional. Professor Michael Jacobides of the London Business School suggested that the exploration of these multiple forms of ecosystems risked emulating Moliere’s “Bourgeois Gentilhomme”, who was surprised and delighted to discover that he has been speaking prose all his life without knowing it.

In the closing session, Julian Birkinshaw, professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at the London Business School, worried about neologisms generally—new words that everyone grabs on to and which become devoid of meaning because they are used in very different ways. And then gradually they lose their meaning. We needed, Birkinshaw said, to work hard to stop people throwing the word, “ecosystem,” into every conversation to sound contemporary and progressive.

‘Ecosystem’ As A New Paradigm For Management

The final panel discussed whether the term “ecosystem” itself might constitute “a changing management paradigm”.

Birkinshaw drew three principal conclusions. First, “there are no new ideas under the sun.” Ideas like the shift competition to collaboration, from centralized to decentralized, from power through authority to power through influence, had antecedents going back not only to Peter Drucker in the 1950s but to Mary Parker Follett in the 1920s. We “had to get over the idea that there would be some huge new idea coming along that we had never thought of.”

Julian Birkinshaw, Professor and Chair of Strategy & Entrepreneurship, London Business School, … [+]

SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST VIA GETTY IMAGES

Second, Birkinshaw suggested that there are no new ideas but lots of new practices in terms of day-to-day experiments. The single most important common theme was that “the value of a firm no longer resides in its existing physical assets and resources.” Competitive advantage no longer resides in the firm’s own assets but rather in “the network of relationships that we have built.” Birkinshaw said that this was a difficult leap for both academics and managers. It was difficult for academics since the “theory of the firm” had been based on the idea that the firm is the unit of analysis. It was difficult for managers to accept that that the value they create through others can be as valuable as what they create under their own intellectual property regime and under their own governance structure. These ideas had existed for a while, but we were now started to see them in reality.

Third, firms were now exploring alternatives to bureaucracy but in different ways. On the one hand, Haier and TenCent were creating a kind of internal market system, trying to free up the complexities of the system and using market mechanisms to give individuals a lot greater opportunity, accountability and a share in the spoils. On the other hand, at Pixar and Tupperware, it was a story of greater community and collectivism, as though trust and personal relationships were at the heart of the modern model of management. Both approaches saw a common bogeyman, bureaucracy, but their solutions sounded different. Birkinshaw wondered whether it was possible to have both community-based and market-based systems, perhaps overlooking the fact that marketplaces have always involved differing degrees of cooperation and competition.

Strategic management scholar Rita McGrath illustrated these propositions with the case of Best Buy, which started losing money after the emergence of on-line sales by Amazon and then resurrected itself by empowering staff, inventing “the shops within a shop,” and matching on-line prices. The connection to the customer and the customer’s issues led to the remarkable turnaround.

MUMBAI, INDIA – APRIL 24: (Editors Note: This is an exclusive shoot of Mint) Rita Gunther McGrath, … [+]

HINDUSTAN TIMES VIA GETTY IMAGES

McGrath noted that in a world where the life expectancy of competitive advantage was getting shorter, innovation and strategy—once very separate—are joining hands. Now you can’t do one without the other. It is the customer journey which ties things together.

Birkinshaw suggested parties are now doing together what they couldn’t do on their own; this had always been the case but digital technology was now enabling us to do this more and better than before. McGrath suggested that the term, “incomplete ecosystem” was a useful way of thinking through what would be needed to deliver value to customers and gave the current example of autonomous automobiles.

Bottom Line

While the conference offered many useful insights on emerging new managerial practices, the effort to articulate a new paradigm of management met with mixed success. Such an effort, to be successful, would require a clearer consensus on what are the management assumptions we are transitioning from as well as on the paradigm that we are moving to. It would also need to shed light on reasons for the gap between the leaders and the laggards in terms of innovation.

Nevertheless, the discussions in Vienna continued to show dramatic changes in the practice of management in the most successful firms today, along three main dimensions; a shift from the goal of the firm to make money for itself towards an obsession with creating more valuable experiences for customers; a shift from top-down bureaucracy towards small autonomous teams; and a shift from vertical, hierarchical modes of organization towards more flexible, horizontal networks or ecosystems. Focusing on only one or two of these three dimensions risks creating misunderstanding or confusion. Firms that handle all three dimensions well are having remarkable success.

[“source=forbes”]