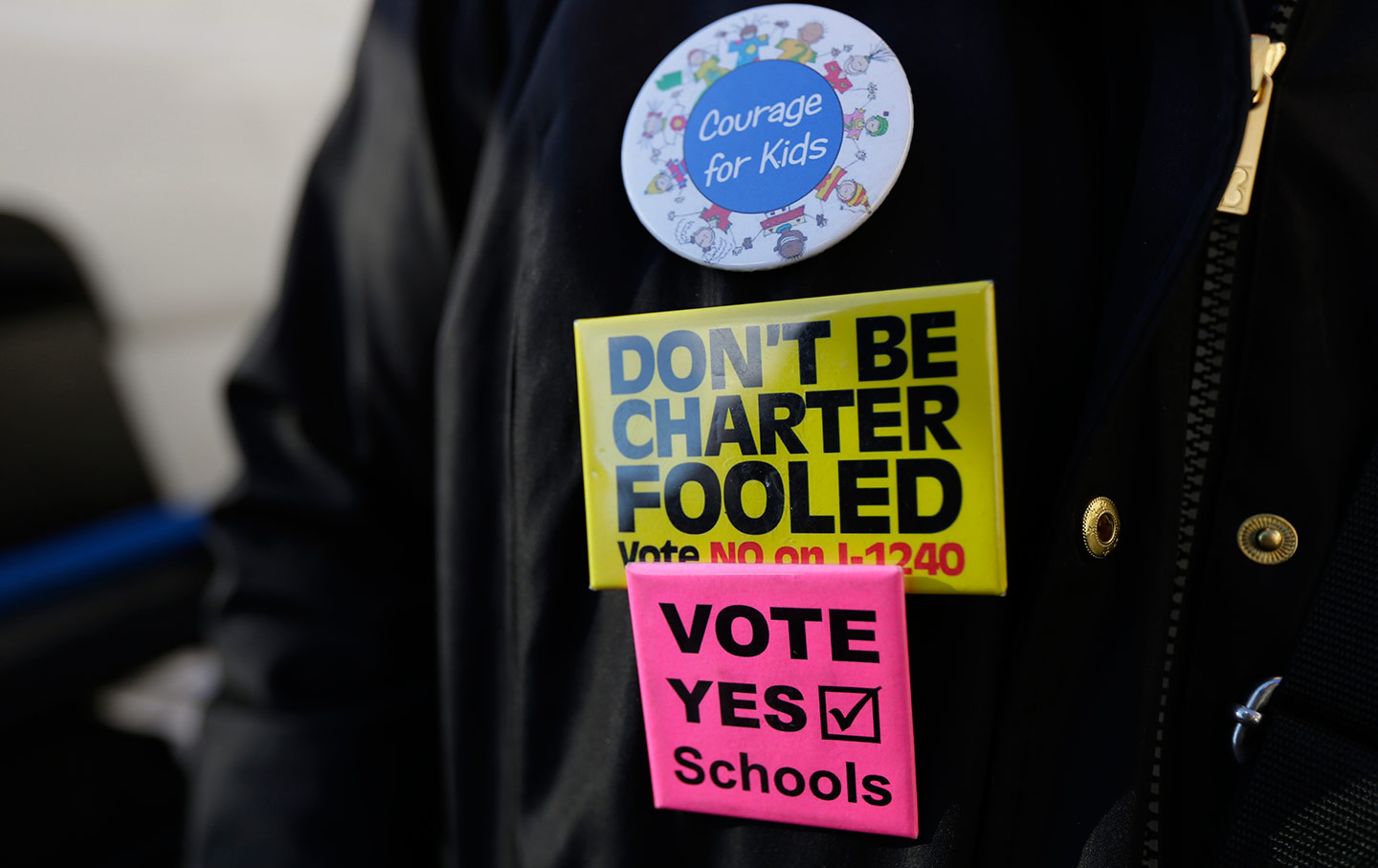

A protester wears buttons opposing charter schools during a protest in Bellevue, Washington, on October 13, 2017. (AP Photo / Ted S. Warren)

Charter schools have been hailed as the antidote to public-school dysfunction by everyone from tech entrepreneurs to Wall Street philanthropists. But a critical autopsy by the advocacy group Network for Public Education (NPE) reveals just how disruptive the charter industry has become—for both students and their communities.

Charter schools are technically considered public schools but are run by private companies or organizations, and can receive private financing—as such, they are generally able to circumvent standard public-school regulations, including unions. This funding system enables maximum deregulation, operating like private businesses and free of the constraints of public oversight, while also ensuring maximum public funding.

According to Carol Burris of NPE, charter schools “want the funding and the privilege of public schools but they don’t want the rules that go along with them.” She cites charter initiatives’ having developed their own certification policies, as well as disciplinary codes and academic standards—a tendency toward “wanting the best of both worlds” among both non- and for-profit charter organizations.

In California, a nonprofit charter industrial model has flourished. The California Virtual Academy (CAVA) network runs hundreds of schools, delivering online-based programs through “cyber” outlets, often concentrated on students in low-income communities of color. CAVA’s political influence has expanded along with its brand.

California’s 2016 primary elections saw fierce battles funded through charter-school industry groups, particularly the Parent Teacher Alliance, which spent several million dollars on races for local superintendents and legislators. Reflecting the ambitions of charter proponents to aggressively expand the sector statewide, the charter boosters pushed candidates who favored lifting district limits on opening new charters. Such policies have sparked controversy, since charter growth is associated with budget erosion for public schools and resistance to staff unionization in the host district. Another measure opposed by the charter sector would “make charter board meetings public, allow the public to inspect charter school records, and prohibit charter school officials from having a financial interest in contracts that they enter into in their official capacity.”

The Los Angeles Unified School District has seen dramatic effects from the expansion of charter schools as it wrestles with budget crises. The teachers’ union recently estimated that charter funding imposes costs on the district of about $590 million annually (the figure is disputed by charter proponents), which to critics affirms that charters receive a growing share of taxpayer funds while leaving regular schools to struggle with chronic funding shortfalls.

The “flexibility” granted to charter schools also drives questionable academic trends. One online charter chain, managed by the Learn4Life network, serves 2,000 students in 15 schools through distance-learning-based programs. But its modular “storefront” teaching system has been accompanied by a churning enrollment with huge attrition rates. According to NPE, in 2015, four-year graduation rates ranged from zero percent in two of its schools, to 19 percent, with an overall average of less than 14 percent making it through all four years.

NPE’s investigation found a similar pattern at a BASIS charter school in Arizona, part of a nationwide charter network. Drawing on an earlier report by the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting, and reflecting the findings of an ACLU investigation into de facto segregation at Arizona charters, NPE argues that, despite heavy private financing, the school falls short in equity. The predominantly white and Asian-American student body of the BASIS Phoenix school contrasts with the high-poverty, mostly Latino surrounding district. With about 200 students total, BASIS Phoenix ultimately graduated just 24 students in 2016, after shedding 44 percent of the graduating grade’s students over the previous four years. The statistics, which matched similar trends across Arizona’s charter sector, suggest charters may actually be perpetuating the discrimination and exclusionary practices that they claim to help remedy.

In response, several school administrators claimed to be striving to address racial disparities. BASIS has forcefully denied that it is abetting inequality in Arizona’s schools, stating that it is “incredibly proud of the diverse nature” of its schools. BASIS.ed also issued a public rebuttal to NPE contending that its chain of schools, overall, maintained high retention rates, did not discriminate by background or ethnicity, and attracted a diverse range of families, as well as donations from them.

But the values of the BASIS network don’t necessarily reflect community diversity. The NPE report cites a third-party analysis of BASIS in a high-profile ranking of schools, America’s Most Challenging High Schools: BASIS Phoenix earned a top rating, according to publisher Jay Mathews, based on standards focused on performance scores. BASIS denies that it unfairly screens out children, citing overall high retention rates across the network for most K–12 classes. But the company, which admits it is “not for everyone” and that students do leave, also promotes a structure that prioritizes retaining high-scoring students, while lower performers realize eventually they can’t meet the standards.

This approach may boost the schools’ business competitiveness, but education advocates who focus on the social goal of providing equitable education for all see it differently. As NPE argues, “there must be a balance between reasonable challenge and inclusivity.” The demographic polarization linked to charter-school expansion, critics warn, exposes the harmful impact of exclusion on diversity: Charters claim to serve diverse populations, but may actually just be segregating the system further.

Examining the broader social impact of charters, NPE tracked financial manipulation and fraud at various schools. In Pennsylvania, lax financial regulations have allowed charters in some districts to absorb extra funding with little oversight. In the New Hope–Solebury School District, for example, the government contributes $19,000 per pupil attending a charter school, even if they are only learning through a screen, since “Those costs must even be paid to cyber charters that have no facilities costs at all.” Another financial question surrounds lopsided pay structures with much higher salaries for charter principals.

Another subsurface problem at many schools is harder to measure: Charters are known for high faculty-turnover rates. Although turnover is a problem in both charter and non-charter schools, NPE’s Burris notes that chaotic management and unregulated expansion, combined with intense academic pressures and high student attrition, can destabilize the whole institution. Traditionally, however, public schools have served as social pillars for the surrounding community. In stable schools, teachers and families grow up together. “Community schools are family schools in many, many ways,” Burris says. “And when they become businesses all of that is destroyed…those relationships are just not there, the way they are in the neighborhood community school.”

Charters may offer a different relationship to communities, but their brand of “free market” schooling carries costs. Who accounts for the lost social opportunities when education becomes just another market investment?

[“Source-thenation”]