After Mrs., a Hindi remake of the Malayalam film The Great Indian Kitchen, was released all over India on the streaming platform Zee5, Indian Twitter plunged into a full-blown meltdown earlier this year. Richa’s life as portrayed in the film is that of a well-educated woman who falls into the monotony of housework after getting married, where her dreams and desires are crushed. I devoured the reviews, but I was unable to watch the movie. Many hailed the movie for its realistic rage against the patriarchy, but the bones of contention that the audience picked with the film were many. A casual Twitter user made the observation that if the husband is the breadwinner, the wife should at least take care of the house. Reading these reviews and blithe takes, I was livid, and I could not quite put a finger on why.

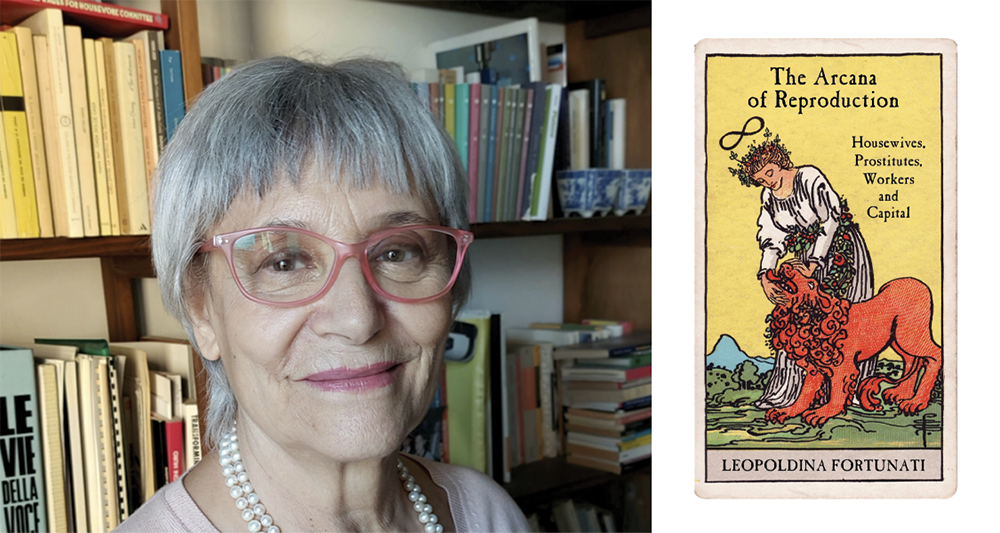

I found the answer, cosmologically-willed, in Leopoldina Fortunati’s work L’arcano della riproduzione (first published in 1981), rendered into English by Arlen Austin and Sara Colantuono as The Arcana of Reproduction. Fortunati was an important member of Lotta Femminista, which was first known as Movimento di Lotta Femminile (Women’s Struggle Movement) and later as Movimento dei Gruppi e Comitati per il Salario al Lavoro Domestico (Movement of Groups and Committees for Wages for Domestic Work). The alternative name, the network of Wages for Housework, is more well-known in English-speaking nations. As the name suggests, the international movement had a militant and anti-capitalist dimension, and its goal to secure pay for housework aligned much with the struggles for wages that were playing out in factories and universities at large. She wrote texts with friends Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, and Silvia Federici that reflected the movement’s goals and ideology; these reflections led to her Arcana of Reproduction. If you decide to read Arcana of Reproduction, you should already be familiar with Marxist jargon. Delving into the text without any prior knowledge of Marxist thought may prove to be a futile exercise, for the very preoccupation of the book is with its theory of reproduction and reproductive labour, in particular the consideration of domestic work and prostitution, as indicated in the book’s subtitle: Housewives, Prostitutes, Workers, and Capital. The work is a practical extension and an important intervention by Fortunati to address Marx’s lopsided consideration of the feminist question, and consequently a response to the male left, achieved by breaking free from the chokehold of theory and situating oneself in reality, the “practical needs of feminist struggle” and the “specific reality of women’s lives.”

Fortunati begins by introducing the structural transition from pre-capitalist to capitalist modes of production, and in doing so, how capitalism underappreciates individual reproduction by prioritising the creation of value. What happens then is the invisibilisation of reproduction next to value, which renders the two separate—almost opposite. In that, reproduction becomes natural and appears as a non-value. The laws that govern production and reproduction are “very different” from one another because the two are thought to be opposites. “Reproduction appears as the mirror image, the photographic negative of production,” according to Fortunati, and the woman is the subject of this negative. It is through this photographic negative that Fortunati sweeps us into understanding the re/production economies of the housewives, the prostitutes, and the workers. Consider the paragraph:

By portraying men and women as unequal participants in capitalism, the paragraph raises questions about the nature of their relationship. Here, Fortunati focuses on the unseen and unacknowledged labor that a woman performs as a housewife or prostitute. They are doubly jeopardised—subservient to capitalism, and subservient to men, the waged male worker. Even in their subservience as housewife or as prostitute, women are not equal, for “woman as housewife is not in an equal relationship with the worker, the prostitute is even less so, because she pays for the money she earns with her own criminalisation.” Fortunati also notes that it was during the Second World War that wage emerged as the site of struggle between the housewife and the waged male worker, where the former demanded that they be handed the paycheck. While the management of paychecks may have been casually dismissed as “a rational management of consumption,” it could mark the first instance of “anti-capitalistic management” of male wage—one that allowed women to think of themselves, however briefly, by booking weekly appointments with their hairdressers.

Fortunati’s thesis is provocative, and particularly so in her chapter “The Hidden Abode: On the Domestic Working Process as a Process of Valorisation,” in which I found the reason for my lividness at the reviews of Mrs. She breaks down the process, starting with the simplest form of labor—procreation—to show that capitalism’s goal is not to take women’s bodies away from them but to take control of them, especially their right to reproduce—their uterus. According to Fortunati, Marx’s critique of capitalism overlooks this crucial aspect of women’s work—the power to perform reproductive tasks. Even love is work, for “domestic labour is not only labour that satisfies, within given limits, the material needs of the individual’s belly, but is also labour that responds to immaterial needs.” She skillfully raises the question of time, bringing to mind Julia Kristeva’s theory of “Women’s Time,” in which the houseworker’s labor power as non-value is chained for an indefinite amount of time. Fortunati examines the affective registers of domesticity using the language of consumption and production, stating that “the man is selfish because he consumes love, while the woman is generous because she produces love.” But how does she produce love? She does not do so freely, outside of a working process, but within the process of domestic labour to produce a commodity: labour power.” When she argues that emotions and sex are “not necessarily natural” and that any emotion we work with as women or consume as men is “fabricated,” Fortunati is at her explosive best. This is demonstrated by the existence of women who refuse to live with men even when they are in a relationship or in love. She extends the logic to filial relationships, such as parents and siblings, in order to draw attention to the imbalance of power within these relationships. These arguments are instrumental in proving her point that capitalism tends to benefit from the servitude of two at the cost of one, and this forms the content of the chapters that follow, where she plunges into Marx’s oeuvre to demystify the question of women’s labour in his writings, thereby attempting to recuperate and bring to the fore the necessity of addressing the reproductive labour of women as productive.

Even though a lot has changed since the book’s conception, Fortunati writes in a fitting afterword that women are not yet freed from the nexus of reproductive work and capitalist relations. This underscores the book’s continued relevance four decades later. For instance, digital mediation, contraception regulation, abortion laws, the failure of the State to regulate laws, and the gendered notion of duty and caregiving abilities are just some of the ways through which women’s work continues to be withheld currency and is consistently undervalued. It is also important to note that Fortunati acknowledges the limitations of her scholarship. She fails to recognize significant interventions and solutions that might have been available through an intersectional lens because she heavily relies on a heteronormative family model. Reading the book was difficult because of the amount of information in it, but Arlen Austin and Sara Colantuono’s skillful translation made it remarkably easy. Reading their translators’ note proved to be the most helpful exercise before I immersed myself in the text. Their existence on the margins—as footnotes—functioned no less than faithful companions, ready to rescue you from the dense abstractions of values, wages, and the broader architecture of textual capitalism. Their timely translation qualifies this book as a work of worthy rumination. While the work is bound to unsettle the sensibilities of certain readers who romanticise matrimony, love, and other sentiments, it may also materialise as an important document to organize, educate, and liberate women—one that speaks to the tarot card on the cover of the book, the Arcanum Eight of Strength, where “your job is to make sure you are talking to yourself with love and support so that you feel safe enough to make different, better choices.”